Lord of the Rings the Towers Book Cover Lord of the Rings All Four Books Art Project

![]()

Cover of the 50th Ceremony I-Book Edition

The Lord of the Rings is an epic high fantasy novel written by J.R.R. Tolkien, which was later fitted as a trilogy. The story began every bit a sequel to Tolkien's before fantasy book The Hobbit, and shortly developed into a much larger story.

Written in stages between 1937 and 1949, with much of it being written during World War II,[1] it was originally published in 3 volumes in 1954 and 1955. Information technology has since been reprinted numerous times and translated into at to the lowest degree 38 different languages,[2] condign one of the virtually popular works in twentieth-century literature.

The action in The Lord of the Rings is set in what the author conceived to be the lands of the existent Earth, inhabited by humanity merely placed in a fictional by, before our history but subsequently the fall of his version of Atlantis, which he chosen Númenor.[3] Tolkien gave this setting a modern English proper name, Middle-earth, a rendering of the Old English Middangeard.[4]

Contents

- 1 Main conflict

- ii Backstory

- 3 Synopsis

- four Characters

- iv.1 Good (excluding most pocket-size characters)

- four.two Evil

- 5 Groundwork

- 5.i Writing

- 5.ii Publication

- 5.3 Publication history

- 5.iv Influences

- 5.5 Critical response

- 6 Adaptations

- 7 Influences on the fantasy genre

- 8 Popular culture references

- ix Farther reading

- x See also

- 10.i Books

- ten.2 Films

- 11 Translations

- 12 References

- 12.1 Text

Main conflict

The story concerns peoples such as Hobbits, Elves, Men, Dwarves, Wizards, and Orcs (called goblins in The Hobbit), and centers on the Band of Power made by the Dark Lord Sauron. Starting from quiet beginnings in the Shire, the story ranges across Middle-earth and follows the courses of the State of war of the Band. The main story is followed by six appendices that provide a wealth of historical and linguistic background textile,[v] as well equally an alphabetize listing every character, place, vocal, and sword.

Forth with Tolkien's other writings, The Lord of the Rings has been subjected to extensive analysis of its literary themes and origins. Although a major work in itself, the story is merely the last motion of a larger mythological cycle, or legendarium, that Tolkien had worked on for many years since 1917.[vi] Influences on this earlier work, and on the story of The Lord of the Rings, include philology, mythology and religion, as well as earlier fantasy works and Tolkien'south experiences in World War I. The Lord of the Rings in its turn is considered to take had a slap-up impact on modern fantasy, and the bear on of Tolkien'south works is such that the use of the words "Tolkienian" and "Tolkienesque" have been recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary.[seven]

The immense and enduring popularity of The Lord of the Rings has led to numerous references in popular civilization, the founding of many societies by fans of Tolkien'south works, and a big number of books nigh Tolkien and his works being published. The Lord of the Rings has inspired (and continues to inspire) brusk stories, video games, artworks and musical works (meet Works inspired by J. R. R. Tolkien). Numerous adaptations of Tolkien's works accept been made for a wide range of media. Adaptations of The Lord of the Rings in particular have been made for the radio, for the theatre, and for picture show. The 2001–2003 release of the Lord of the Rings picture show trilogy saw a surge of involvement in The Lord of the Rings and Tolkien'due south other works.[viii]

Backstory

The back story begins thousands of years before the action in the book, with the ascent of the eponymous Lord of the Rings, the Dark Lord Sauron, a malevolent reincarnated deity who possessed great supernatural powers and who later became the ruler of the dreaded realm of Mordor. At the cease of the First Age of Centre-earth, Sauron survived the catastrophic defeat and chaining of his lord, the ultimate Dark Lord, Morgoth (who was formerly counted as one of the Valar, the angelic Powers of the earth). During the 2nd Age, Sauron schemed to proceeds dominion over Middle-earth. In the disguise every bit "Annatar" or Lord of Gifts, he aided Celebrimbor and other Elven-smiths of Eregion in the forging of magical Rings of Power which conferred various powers and effects on their wearers. The most of import of these were the Nine, the 7 and the Iii (which he did not touch or know of the three.) called the Rings of Power or Corking Rings.

However, he then secretly forged a Nifty Ring of his own, the One Ring, by which he planned to enslave the wearers of the other Rings of Ability. This program failed when the Elves became aware of him and took off their Rings. Sauron then launched a war during which he captured xvi and distributed them to lords and kings of Dwarves and Men; these Rings were known as the Seven and Ix respectively. The Dwarf-lords proved besides tough to be enslaved, although their natural want for wealth, especially gold, increased; this brought more conflict betwixt them and other races, and fed a dangerous greed. The Men who received the 9 ringts were slowly corrupted over fourth dimension and eventually became the Nazgûl, Sauron's most feared servants. The Three Rings Sauron failed to capture, and remained in the possession of the Elves (who forged these independently). The war concluded as Men of the island-kingdom of Númenor helped the besieged Elves, and Sauron's forces retreated from the coasts of Eriador. At this time he still held most of Centre-globe, excluding Imladris (Rivendell) and the Gulf of Lune.

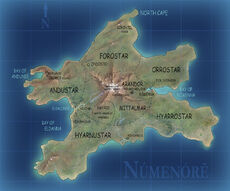

A map of Númenor (called Andor by the Elves)

Over 1500 years later, word reached the King of Númenor, Ar-Pharazôn, that Sauron had claimed the title "King of Men". This provoked Ar-Pharazôn and gave him an opportunity to display the glory and strength of Númenor. He arrived in Middle-globe with such overwhelming force that Sauron's armies fled at the sight of the Númenóreans. Abandoned by his minions, Sauron surrendered to the Númenóreans, and was taken to Númenor equally a "prisoner". Sauron then started to poison the minds of the Númenóreans confronting the Valar. Thus, Sauron fix into motion events that brought about Númenor's destruction. He did this past corrupting the King's mind, telling him that the immortality of the Elves was his to accept if he gear up human foot upon the lands of Aman, the Blessed Realm, where Valinor, the realm of the Valar, was located. Fearing death, Ar-Pharazôn led an invasion of Aman and Valinor with the greatest host seen since the end of the First Age. However, upon reaching Aman, he and his ground forces were buried by a landslide, and there they would remain until the Terminal Boxing in Tolkien's eschatology. Manwë, the King of Arda, chosen upon Eru Ilúvatar (God), who opened a smashing chasm in the sea, destroying Númenor, and removed the Undying Lands from the mortal world. The destruction of Númenor destroyed Sauron'south physical trunk and his ability to have a fair and handsome shape, but his spirit returned to Mordor and assumed a new form: black, "burning hot", and terrible.

Over 100 years later on, he launched an attack against the Númenórean exiles (The Faithful, who did not bring together Ar-Pharazôn'south expedition), who managed to escape to Middle-earth. However, the exiles (led by Elendil and his sons Isildur and Anárion) had time to prepare, and, after forming the Last Alliance of Elves and Men with the Elven-king Gil-galad, they marched against Mordor, defeated Sauron on the plain of Dagorlad, and besieged Barad-dûr, at which time Anárion was slain. Later on 7 years of siege, Sauron himself was ultimately forced to engage in single combat with the leaders. Gil-galad and Elendil perished in the struggle, and Elendil'south sword, Narsil, broke beneath him. However, Sauron's trunk was also overcome and slain,[3] and Isildur cut the One Band from Sauron's manus with the hilt-shard of Narsil, and at this Sauron's spirit fled and he did non reappear for a millenium. Isildur was advised to destroy the One Ring by the merely mode it could be — by casting it into the volcanic Mount Doom where it was forged — just he refused, attracted to its beauty and kept it as compensation for the deaths of his father and brother (weregild).

So began the Third Age of Middle-earth. Two years later, while journeying to Rivendell, Isildur and his soldiers were ambushed by a ring of Orcs at the Disaster of the Gladden Fields. While the latter were well-nigh all killed, Isildur escaped by putting on the Ring — which made mortal wearers invisible. However, the Ring slipped from his finger while he was pond in the great River Anduin; he was killed by Orc-arrows and the Ring was lost for 2 millennia. It was then found by run a risk by a Stoor named Déagol. His relative and friend[3] Sméagol strangled him for the Band and was banished from his home by his maternal grandmother. He fled to the Misty Mountains where he slowly withered and became a disgusting, slimy creature called Gollum.

In The Hobbit, gear up lx years before the events in The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien relates the story of the seemingly accidental finding of the Ring by some other hobbit, Bilbo Baggins, who takes it to his dwelling, Bag End. Story-externally, the tale related in The Hobbit was written before The Lord of the Rings, and it was only later that the author developed Bilbo's magic ring into the "I Ring." Neither Bilbo nor the sorcerer, Gandalf, are aware at this point that Bilbo's magic band is the Ane Ring, forged past the Dark Lord Sauron.

Synopsis

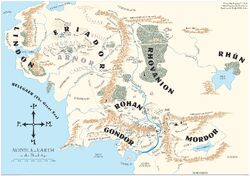

Middle-earth during the Third Age

The Lord of the Rings takes upwardly the story about sixty years after the end of The Hobbit. The story begins in the first book, The Fellowship of the Ring, when Frodo Baggins, Bilbo'southward adoptive heir, came into possession of Bilbo's magic ring. Bilbo's old friend, Gandalf the Grey, who got Bilbo involved in the adventures in The Hobbit that led to the discovery of the Band, discovered that it was in fact the Ane Band, the instrument of Sauron's ability and the object for which the Dark Lord has been searching for about of the Third Age, and which corrupted others with desire for information technology and the power information technology held.

Sauron sent the sinister Nazgûl, in the guise of riders in blackness, to the Shire, Frodo'due south native land, in search of the Ring. Frodo escaped, with the help of his loyal gardener Samwise Gamgee and 3 close friends, Meriadoc Brandybuck, Peregrin Took, and Fredegar Bolger. While Fredegar acted every bit decoy for the Ringwraiths, Frodo and the others set off to take the Ring to the Elven haven of Rivendell. They were aided by the enigmatic Tom Bombadil, who saved them from Erstwhile Man Willow and took them in for a few days of feasting, residue, and counsel. At the boondocks of Bree, Frodo'due south political party was joined by a man chosen "Strider", who was revealed, in a letter left by Gandalf at the local inn for Frodo, to be Aragorn, the heir to the thrones of Gondor and Arnor, 2 swell realms founded by the Númenórean exiles. Aragorn led the hobbits to Rivendell on Gandalf's request. However, Frodo was gravely wounded past the leader of the Ringwraiths, though he managed to recover under the intendance of the Half-elven lord Elrond.

In Rivendell, the hobbits also learned that Sauron's forces could simply be resisted if Aragorn took upward his inheritance and fulfilled an ancient prophecy by wielding the sword Andúril, which had been forged anew from the shards of Narsil, the sword that cut the Band from Sauron's finger in the Second Historic period. The treachery of Saruman, formerly caput of the White Council and now in league with Sauron is likewise revealed. A high quango, attended by representatives of the major races of Middle-globe; Elves, Dwarves, and Men, and presided over by Elrond, decide that the only course of action that tin save Eye-earth is to destroy the Band by taking it to Mordor and casting it into Mountain Doom, where it was forged.

Frodo volunteered for the task, and a "Fellowship of the Ring" was formed to aid him — consisting of Frodo, his iii Hobbit companions, Gandalf, Aragorn, Boromir of Gondor, Gimli the Dwarf, and Legolas the Elf. Their journey took them through the Mines of Moria, where they began to be followed past the creature Gollum, whom Bilbo had met in the Goblin-caves of the Misty Mountains years before. (The full tale of their meeting is told in The Hobbit.) Gollum long possessed the Ring before it passed to Bilbo. Gandalf explained that Gollum belonged to a people "of hobbit-kind" before he came upon the Band, which corrupted him. A slave to the Ring'due south evil power, Gollum desperately sought to regain his "Precious." Every bit they proceeded through the Mines, Pippin unintentionally betrayed their presence and the party was attacked past creatures of Sauron. Gandalf battled an aboriginal demon, a Balrog, and roughshod into a deep chasm, apparently to his death. Escaping from Moria, the Fellowship, now led by Aragorn, go to the Elven realm of Lothlórien. Here, the Lady Galadriel showed Frodo and Sam visions of the past, present, and future. Frodo likewise saw the Eye of Sauron, a metaphysical expression of Sauron himself, and Galadriel was tempted by the Ring. By the terminate of the first volume, afterwards the Fellowship has travelled along the great River Anduin, Frodo decided to continue the expedition to Mordor on his own, largely due to the Ring's growing influence on Boromir; however, the faithful Sam insisted on going with him.

In the 2d volume, The Two Towers, a parallel story, told in the outset book of the volume, details the exploits of the remaining members of the Fellowship who assistance the state of Rohan in its war against the emerging evil of Saruman, leader of the Order of Wizards, who wanted the Ring for himself. At the start of the start book, the Fellowship was further scattered; Merry and Pippin were captured by Sauron and Saruman's Orcs, Boromir was mortally wounded defending them, and Aragorn and the others went off in pursuit of the Hobbits captors. The iii come across Gandalf, who has returned to Middle-earth as "Gandalf the White": they plant out that he slew the Balrog of Moria, and although the battle also proved fatal to Gandalf, he was then sent back and "reborn" as a more than imposing figure. At the end of the first book, Gandalf, Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli help defeat Saruman's armies at the Battle of the Hornburg while Saruman himself was cornered by the tree-similar Ents and Huorns, accompanied past Merry and Pippin, who escaped from captivity, and the two groups are reunited.

The second book of the book tells of Frodo and Sam's exploits on the mode to Mountain Doom. They managed to capture and "tame" Gollum, who then showed them a manner to enter Mordor secretly (as opposed to the Black Gate), admitting through the dreaded realm of Minas Morgul. At the end of the volume, Gollum betrayed Frodo to the great spider, Shelob, and though he survived, he was captured by Orcs. Meanwhile, Sauron launched an all-out military assail upon Center-earth, with the Witch-king (leader of the Ringwraiths) leading a cruel host from Minas Morgul into battle against Gondor, in the War of the Ring.

In the third volume, The Return of the Rex, the farther adventures of Gandalf, Aragorn and visitor are related in the get-go book of the book, while Frodo and Sam's are related in the second, equally with The Two Towers. Every bit told in the first book, the Fellowship assisted in the final battles against the armies of Sauron, including the siege of the metropolis of Minas Tirith in Gondor and the climactic life-or-death boxing before the Black Gate of Mordor, where the brotherhood of Gondor and Rohan fought desperately confronting Sauron'due south armies in society to distract him from the Ring, hoping to proceeds time for Frodo to destroy it.

In the second book, Sam rescued Frodo from captivity. Later much struggle, they finally reached Mount Doom itself, tailed by Gollum. Yet, the temptation of the Ring proved too great for Frodo and he claimed information technology for himself. However, Gollum struggled with him and managed to bite the Ring off. Crazed with triumph, Gollum slipped into the fires of the mountain, and the Ring was destroyed.

Finally, Sauron was defeated, and Aragorn was crowned rex. However, all was non over, for Saruman managed to escape and scour the Shire earlier being overthrown. At the end, Frodo remained wounded in body and spirit and went westward accompanied by Bilbo over the Ocean to Valinor, where he could notice peace.

According to Tolkien's timeline, the events depicted in the story occurred between Bilbo'southward announcement of his September 22, 3001 birthday party, and Sam'due south return to Pocketbook End on October 6, 3021. Most of the events portrayed in the story occur in TA 3018 and TA 3019, with Frodo heading out from Pocketbook End on September 23 3018, and the destruction of the Band 6 months afterwards on March 25, 3019.

Characters

- For character information see: List of characters

Good (excluding most minor characters)

- Aragorn

- Gimli

- Legolas

- Gandalf

- Boromir

- Frodo Baggins

- Samwise Gamgee

- Peregrin Took

- Meriadoc Brandybuck

- Bilbo Baggins

- Elrond

- Glorfindel

- Arwen

- Elladan

- Elrohir

- Thranduil

- Haldir

- Celeborn

- Galadriel

- Gwaihir

- Balin (mentioned)

- Glóin

- Dáin II Ironfoot (mentioned)

- Faramir

- Denethor II

- Beregond

- Treebeard

- Théoden

- Éomer

- Éowyn

- Háma

- Gamling

- Théodred

Evil

- Sauron

- Witch-rex of Angmar

- Mouth of Sauron

- Nazgûl

- Gorbag

- Shagrat

- Saruman

- Gríma Wormtongue

- Uglúk

- Gollum

- Shelob

- Durin's Bane, a Balrog

Background

Writing

| The Lord of the Rings |

|---|

| Volume I - Book Ii - Volume Three |

The Lord of the Rings in conception was meant every bit a sequel The Hobbit, his tale for children published in 1937.[9] The popularity of The Hobbit led to demands from his publishers for more stories almost Hobbits and goblins, and so that same year Tolkien began writing what would become The Lord of the Rings - non to exist finished until 12 years afterward in 1949, not exist fully published until 1955, by which fourth dimension Tolkien would be 63 years old.

Tolkien did not originally intend to write a sequel to The Hobbit, and instead wrote several other children'south tales such every bit Roverandom. As his main piece of work, Tolkien began to outline the history of Arda, telling tales of the Silmarils, and many other stories forming the vast background to The Lord of the Rings and the Third Age. Tolkien died earlier he could complete and put together all of this piece of work cohesively, simply his son Christopher Tolkien edited his father's work, filled in gaps, and published it in 1977 as The Silmarillion.[10] Some Tolkien biographers regard The Silmarillion as the truthful "work of his heart"[11], as it provides the historical and linguistic context for the more popular work and for his constructed languages, and had occupied most of Tolkien's adult life. As a effect The Lord of the Rings concluded upwardly as the last movement of Tolkien's legendarium and, to him, the "much larger, and I hope also in proportion the best, of the entire bike".[3]

Persuaded by his publishers, he started 'a new Hobbit' in the 3rd week of December 1937.[12] Afterward several faux starts, the story of the One Ring shortly emerged, and the book mutated from being a sequel to The Hobbit, to beingness, in theme, more a sequel to the unpublished Silmarillion. The idea of the first chapter (A Long-expected Party) arrived fully-formed, although the reasons backside Bilbo'southward disappearance, the significance of the Ring, and the title The Lord of the Rings did non arrive until the bound of 1938.[9] Originally, he planned to write another story in which Bilbo had used up all his treasure and was looking for another adventure to gain more; withal, he remembered the band and its powers and decided to write virtually it instead.[9] He began with Bilbo as the principal graphic symbol but decided that the story was too serious to use the fun-loving hobbit and so Tolkien looked to employ a member of Bilbo's family unit.[9] He thought virtually using Bilbo's son, but this generated some difficult questions, such equally the whereabouts of his wife and whether he would permit his son become into danger. Thus he looked for an alternating character to carry the ring. In Greek legend, it was a hero's nephew that gained the item of power, then the hobbit Frodo came into beingness.[9]

- "As the high Legends of the commencement are supposed to look at things through Elvish minds, then the middle tale of the Hobbit takes a virtually human point of view - and the last tale [The Lord of the Rings] blends them."

- —Tolkien on The Silmarillion, The Hobbit, and The Lord of the Rings respectively[13]

Writing was slow due to Tolkien's perfectionism and a wartime shortage of newspaper. It was oft interrupted by his obligations as an examiner, and other academic duties.

The first sentence of The Hobbit was in fact written on a blank page which a educatee had left on an exam paper which Tolkien was marking — "In a pigsty in the basis there lived a hobbit."[xiv] He seems to have abandoned The Lord of the Rings during most of 1943 and only restarted it in April 1944.[ix] This effort was written as a serial for Christopher Tolkien and C.S. Lewis — the erstwhile would exist sent copies of capacity as they were written while he was serving in Africa in the Royal Air Force. He made another push in 1946, and showed a copy of the manuscript to his publishers in 1947.[9] The story was effectively finished the next twelvemonth, but Tolkien did not cease revising earlier parts of the work until 1949.[9]

A dispute with his publishers, Allen & Unwin, led to the book existence offered to HarperCollins in 1950. He intended The Silmarillion (itself largely unrevised at this point) to be published along with The Lord of the Rings, but A&U were unwilling to do this. After his contact at Collins, Milton Waldman, expressed the conventionalities that The Lord of the Rings itself "urgently needed cut", he eventually demanded that they publish the book in 1952. They did not practice then, and so Tolkien wrote to Allen and Unwin, saying "I would gladly consider the publication of any part of the stuff."[9]

Publication

For publication, due largely to mail-state of war paper shortages, but also to keep the price of the first volume down, the book was divided into three volumes: The Fellowship of the Band: Books I and Two, The Two Towers: Books Iii and IV, and The Return of the King: Books V and VI plus 6 appendices. Delays in producing appendices, maps and especially indices led to these existence published afterwards than originally hoped — on 21 July 1954, eleven November 1954 and 20 October 1955 respectively in the United Kingdom, slightly later in the The states. The Return of the King was particularly delayed. Tolkien, moreover, did not especially like the championship The Return of the King, assertive information technology gave away too much of the storyline. He had originally suggested State of war of the Ring, which was dismissed past his publishers.[15]

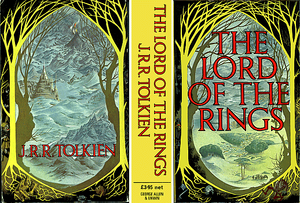

Dust jacket of the 1968 UK edition

The books were published under a 'profit-sharing' arrangement, whereby Tolkien would not receive an advance or royalties until the books had cleaved even, later which he would accept a large share of the profits. An index to the entire three-volume set up at the end of third volume was promised in the first volume. However, this proved impractical to compile in a reasonable timescale. Later, in 1966, 4 indices, not compiled by Tolkien, were added to The Render of the Rex. Considering the three-book binding was so widely distributed, the piece of work is oft referred to as the Lord of the Rings "trilogy." In a letter to W. H. Auden, Tolkien himself made use of the term "trilogy" for the work (The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, #163) though he did at other times consider this incorrect, as it was written and conceived as a unmarried book (Letters, #149). It is too often called a novel; however, Tolkien also objected to this term as he viewed it as a romance (Letters, #329; "romance" in this sense refers to a heroic tale).

A 1999 (Millennium Edition) British (ISBN 0-261-10387-3) seven-volume box ready followed the half-dozen-book partition authored by Tolkien, with the Appendices from the end of The Render of the King bound as a separate volume. The messages of Tolkien appeared on the spines of the boxed set which included a CD. To coincide with the moving picture release, a new version of this pop edition was released featuring images from the films, such equally:

- I - Frodo climbing the steps to Pocketbook End

- II - Aragorn and Arwen in Rivendell

- Iii - Gandalf in Moria

- Iv - A swan boat from Lothlórien

- Five - A Black Rider from the 'Flight to the Ford' sequence

- VI - The belfry of Cirith Ungol (although this image featured in many of the promotional books (e.1000. the 'FotR Photo Guide') from the kickoff motion-picture show, it did not characteristic in the films until Render of the King)

- App. - Frodo's hand holding the One Ring

This new banner (ISBN 0-00-763555-ix) also omitted the CD. The individual names for books in this series were decided posthumously, based on a combination of suggestions Tolkien had fabricated during his lifetime and the titles of the existing volumes — viz:

- T Book I: The Render of the Shadow

- O Book Ii: The Fellowship of the Ring

- L Book Iii: The Treason of Isengard

- Grand Volume Iv: The Journey to Mordor

- I Volume V: The War of the Ring

- E Volume Half-dozen: The Return of the King

- Due north Appendices

The name of the complete work is often abbreviated to 'LotR', 'LOTR', or but 'LR' (Tolkien himself used L.R.), and the three volumes as FR, FOTR, or FotR (The Fellowship of the Ring), TT or TTT (The Two Towers), and RK, ROTK, or RotK (The Return of the King).

Note that the titles The Return of the Shadow, The Treason of Isengard and The War of the Ring were used by Christopher Tolkien in The History of The Lord of the Rings.

Publication history

The three parts were starting time published by Allen & Unwin in 1954–1955, several months apart. They accept since been reissued many times by multiple publishers, as ane, three, six or seven volume sets. The two most common current printings are ISBN 0-618-34399-vii (one-volume) and ISBN 0-618-34624-4 (3 book set). In the early on 1960s, Donald A. Wollheim, science fiction editor of the paperback publisher Ace Books, realized that The Lord of the Rings was not protected in the United states of america nether American copyright constabulary because the Us hardcover edition had been spring from pages printed in the United Kingdom, with the original intention being for them to be printed in the British edition. Ace Books proceeded to publish an edition, unauthorized by Tolkien and without royalties to him. Tolkien took consequence with this and apace notified his fans of this objection. Grass-roots force per unit area from these fans became so great that Ace books withdrew their edition and made a nominal payment to Tolkien, well below what he might have been due in an appropriate publication. Withal, this poor beginning was overshadowed when an authorized edition followed from Ballantine Books to tremendous commercial success. Past the mid-1960s the books, due to their wide exposure on the American public phase, had become a true cultural phenomenon. Too at this time Tolkien undertook various textual revisions to produce a version of the volume that would have a valid US copyright. This would afterwards go known as the Second Edition of The Lord of the Rings.

The books accept been translated, with various degrees of success, into dozens of other languages.[xvi] Tolkien, an expert in philology, examined many of these translations, and had comments on each that reflect both the translation process and his work. To aid translators, Tolkien wrote his Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings. Because The Lord of the Rings is said to be a translation of the Cherry-red Book of Westmarch, translators have an unusual degree of liberty when translating The Lord of the Rings. This allows for such translations as Elf becoming Elb in German — Elb does not bear the connotations of mischief that its English counterpart does and therefore is more true to the work that Tolkien created. In dissimilarity to the usual mod practice, names intended to have a particular pregnant in the English language version are translated to provide a similar pregnant in the target language: in German, for example, the proper name "Baggins" becomes "Beutlin," containing the give-and-take Beutel pregnant "bag."

In 1990 Recorded Books published an entire sound version of the books, and hired British actor Rob Inglis, who had starred in a one-homo production of The Hobbit, to read. Inglis performs the books verbatim, using distinct voices for each grapheme, and sings all of the songs. Tolkien had written music for some of the songs in the book. For the rest, Inglis, along with managing director Claudia Howard wrote boosted music. The electric current ISBN is 1402516274.

Influences

The Lord of the Rings began as a personal exploration by Tolkien of his interests in philology, faith (particularly Roman Catholicism), fairy tales, as well as Norse and Celtic mythology, but it was also crucially influenced by the effects of his war machine service during World War I.[17] Tolkien detailed his creation to an phenomenal extent; he created a complete mythology for his realm of Eye-earth, including genealogies of characters, languages, writing systems, calendars and histories. Some of this supplementary material is detailed in the appendices to The Lord of the Rings, and the mythological history woven into a big, biblically-styled book entitled The Silmarillion. Yet many parts of the world he crafted, equally he freely admitted, are influenced past other sources.

Tolkien's largest influences in the creation of his world were his Catholic religion and the Bible.[18] Tolkien once described The Lord of the Rings to his friend, the English Jesuit Father Robert Murray, as "a fundamentally religious and Catholic work, unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision."[3] At that place are many theological themes underlying the narrative including the battle of skilful versus evil, the triumph of humility over pride, and the activity of grace. In addition the saga includes themes which incorporate death and immortality, mercy and pity, resurrection, salvation, repentance, cocky-sacrifice, free will, justice, fellowship, authority and healing. In addition the Lord'south Prayer "And lead us not into temptation, just deliver us from evil" was reportedly present in Tolkien'south mind every bit he described Frodo's struggles confronting the power of the One Ring.[3]

Not-Christian religious motifs also had stiff influences in Tolkien's Middle-globe. His Ainur, a race of angelic beings who are responsible for conceptualising the world, includes the Valar, the pantheon of "gods" who are responsible for the maintenance of everything from skies and seas to dreams and doom, and their servants, the Maiar. The concept of the Valar echoes Greek and Norse mythologies, although the Ainur and the earth itself are all creations of a monotheistic deity — Ilúvatar or Eru, "The One". Every bit the external practice of Middle-earth religion is downplayed in The Lord of the Rings, explicit data about them is merely given in the different versions of Silmarillion material. However, there remain allusions to this aspect of Tolkien's mythos, including "the Not bad Enemy" who was Sauron's master and "Elbereth, Queen of Stars" (Morgoth and Varda respectively, two of the Valar) in the main text, the "Authorities" (referring to the Valar, literally Powers) in the Prologue, and "the I" in Appendix A. Other non-Christian mythological elements tin be seen, including other sentient non-humans (Dwarves, Elves, Hobbits and Ents), a "Green Man" (Tom Bombadil), and spirits or ghosts (Barrow-wights, Oathbreakers).

Gandalf the "Odinic wanderer", from a book cover by John Howe

The mythologies from northern Europe are perhaps the best known non-Christian influences on Tolkien. His Elves and Dwarves are mostly based on Norse and related Germanic mythologies.[ citation needed ] The figure of Gandalf is particularly influenced by the Germanic deity Odin in his incarnation as "the Wanderer", an old man with one eye, a long white bristles, a broad brimmed hat, and a staff; Tolkien states that he thinks of Gandalf as an "Odinic wanderer" in a letter of 1946.[three] Finnish mythology and more than specifically the Finnish national epic Kalevala were also acknowledged by Tolkien as an influence on Middle-world. [ citation needed ] In a similar style to The Lord of the Rings, the Kalevala centers around a magical item of keen power, the Sampo, which bestows nifty fortune on its owner but never makes its exact nature articulate. Like the I Band, the Sampo is fought over past forces of skillful and evil, and is ultimately lost to the world as it is destroyed towards the end of the story. In another parallel, the latter work's wizard character Väinämöinen also has many similarities to Gandalf in his immortal origins and wise nature, and both works cease with their respective wizard parting on a ship to lands beyond the mortal world. Tolkien also based his Elvish language Quenya on Finnish.[19]

In addition The Lord of the Rings was crucially influenced by Tolkien'southward experiences during Earth War I and his son's during World War Two. The key action of the books — a climactic, age-ending war between good and evil — is the central event of many earth mythologies, notably Norse, but it is also a articulate reference to the well-known clarification of Globe State of war I, which was commonly referred to every bit "the state of war to end all wars." After the publication of The Lord of the Rings these influences led to speculation that the I Ring was an apologue for the nuclear bomb.[20] Tolkien, yet, repeatedly insisted that his works were not an apologue of any kind. However there is a potent theme of despair in the face of new mechanized warfare that Tolkien himself had experienced in the trenches of Earth State of war I. The development of a specially bred Orc army, and the destruction of the environment to aid this, also have modern resonances; and the effects of the Band on its users evoke the modernistic literature of drug addiction as much equally whatsoever historic quest literature.

Nevertheless, Tolkien states in the introduction to the books that he disliked allegories and that the story was not one,[21] and it would be irresponsible to dismiss such straight statements on these matters lightly. Tolkien had already completed well-nigh of the book, including the ending in its entirety, before the first nuclear bombs were fabricated known to the world at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

While Tolkien plausibly denied any specific 'nuclear' reference, it is articulate that the Band has wide applicability to the concept of Absolute Ability and its furnishings, and that the plot hinges on the view that anyone who seeks to proceeds absolute worldly power will inevitably be corrupted by it. Some also say there is too articulate show that one of the chief subtexts of the story — the passing of a mythical "Golden Age" — was influenced not only by Arthurian legend simply besides by Tolkien's contemporary anxieties virtually the growing encroachment of urbanisation and industrialisation into the "traditional" English language lifestyle and countryside. The concept of the "ring of power" itself is also present in Plato'southward Republic and in the story of Gyges' ring (a story often compared to the Book of Task). Many, however, believe Tolkien's well-nigh probable source was the Norse tale of Sigurd the Volsung. Some locations and characters were inspired past Tolkien's childhood in Sarehole (then a Worcestershire village, now office of Birmingham) and Birmingham.

Disquisitional response

Tolkien's work has received mixed reviews since its inception, ranging from terrible to excellent. Recent reviews in various media have been, in a majority, highly positive. On its initial review the Sun Telegraph felt it was "among the greatest works of imaginative fiction of the twentieth century". The Dominicus Times seemed to echo these sentiments when in their review it was stated that "the English-speaking earth is divided into those who have read The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit and those who are going to read them." The New York Herald Tribune also seemed to have an idea of how pop the books would go, writing in its review that they were "destined to outlive our time."[22]

Not all original reviews, notwithstanding, were then kind. New York Times reviewer Judith Shulevitz criticized the "pedantry" of Tolkien's literary style, maxim that he "formulated a loftier-minded conventionalities in the importance of his mission as a literary preservationist, which turns out to be death to literature itself." [23] Critic Richard Jenkyns, writing in The New Republic, criticized a perceived lack of psychological depth. Both the characters and the work itself are, according to Jenkyns, "anemic, and lacking in fiber."[24] Even within Tolkien's social group, The Inklings, reviews were mixed. Hugo Dyson was famously recorded as saying, during one of Tolkien'south readings to the grouping, "Oh no! Not another fucking elf!"[25] Withal, another Clue, C.S. Lewis, had very different feelings, writing, "here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn down like cold iron. Hither is a volume which volition break your heart."

Several other authors in the genre, however, seemed to agree more with Dyson than Lewis. Science-fiction writer David Brin criticized the books for what he perceived to exist their unquestioning devotion to a traditional elitist social structure, their positive depiction of the slaughter of the opposing forces, and their romantic backward-looking worldview.[26] Michael Moorcock, another famous science fiction and fantasy writer, is also a fervent detractor of The Lord of the Rings. In his essay, "Epic Pooh," he equates Tolkien's piece of work to Winnie-the-Pooh and criticizes information technology and similar works for their perceived Merry England point of view.[27] Incidentally, Moorcock met both Tolkien and Lewis in his teens and claims to have liked them personally, even though he does not adore them on artistic grounds.

More than recently, critical analysis has focused on Tolkien'southward experiences in the Outset World War; writers such every bit John Garth in 'Tolkien and the Great War', Janet Brennan Croft and Tom Shippey all look in detail at this attribute and compare the imagery, mental mural and traumas in Lord of the Rings with those experienced past soldiers in the trenches and the history of the Great War. John Carey, formerly Merton Professor of English Literature at Oxford Academy, speaking in April 2003 on the BBC "Big Read" plan which voted Lord of the Rings "Britain's all-time-loved book", said that "Tolkien's writing is essentially a species of war literature; not as directly mayhap every bit Wilfred Owen, or every bit solid as some, just very, very interesting as that — the most solid reflection on war experiences written upwards as fantasy."

The Lord of the Rings, despite not existence published in paperback until the 1960s, sold well in hardback.[28] In 1957 it was awarded the International Fantasy Honour. Despite its numerous detractors, the publication of the Ace Books and Ballantine paperbacks helped The Lord of the Rings become immensely pop in the 1960s. The volume has remained so ever since, ranking as one of the most pop works of fiction of the twentieth century, judged past both sales and reader surveys.[29] In the 2003 "Large Read" survey conducted by the BBC, The Lord of the Rings was found to be the "Nation'due south All-time-loved Book". Australians voted The Lord of the Rings "My Favourite Volume" in a 2004 survey conducted by the Australian ABC.[30] In a 1999 poll of Amazon.com customers, The Lord of the Rings was judged to exist their favourite "book of the millennium".[31] In 2002 Tolkien was voted the ninety-2d "greatest Briton" in a poll conducted past the BBC, and in 2004 he was voted thirty-fifth in the SABC3'south Great South Africans, the only person to appear in both lists. His popularity is not express only to the English-speaking world: in a 2004 poll inspired by the UK's "Big Read" survey, most 250,000 Germans found The Lord of the Rings to exist their favourite work of literature.[32]

Adaptations

- Main commodity: Adaptations of The Lord of the Rings

Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring

The Lord of the Rings has been adjusted for film, radio and phase multiple times.

The volume has been adapted for radio three times. In 1955 and 1956, the British Broadcasting Company (BBC) broadcast The Lord of the Rings, a 12-part radio adaptation of the story, of which no recording has survived. A 1979 dramatization of The Lord of the Rings was circulate in the United States and subsequently issued on tape and CD. In 1981 the BBC circulate, The Lord of the Rings, a new dramatization in 26 half-hour installments.

Three film adaptations have been made. The showtime was J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings (1978), past animator Ralph Bakshi, the outset office of what was originally intended to be a two-part accommodation of the story (hence its original title, The Lord of the Rings Part i). It covers The Fellowship of the Ring and part of The Two Towers. The 2d, The Return of the Male monarch (1980), was an blithe tv special by Rankin-Bass, who had produced a similar version of The Hobbit (1977). The third was managing director Peter Jackson's live action The Lord of the Rings pic trilogy, produced by New Line Cinema and released in three installments every bit The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002), and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003). The alive-action film trilogy has done much in particular to bring the book into the public consciousness.[8]

In that location have been four stage productions based on the volume. Three original full-length stage adaptations of The Fellowship of the Band (2001), The Two Towers (2002), and The Return of the King (2003) were staged in Cincinnati, Ohio. A stage musical adaptation of The Lord of the Rings (2006) was staged in Toronto, Canada.

Influences on the fantasy genre

Following the massive success of The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien considered a sequel entitled The New Shadow, in which the Men of Gondor plow to dark cults and consider an insurgence confronting Aragorn's son, Eldarion. Tolkien decided not to do it, and the incomplete story can exist found in The Peoples of Middle-earth. Tolkien returned to finish his mythology, which was published in novel form posthumously by Christopher Tolkien in 1977, and the remaining information of his legendarium was published through Unfinished Tales (1980) and The History of Middle-globe, a 12 volume series published from 1983 to 1996, of which The Peoples of Center-earth is part.

Nonetheless, the enormous popularity of Tolkien's epic saga greatly expanded the demand for fantasy fiction. Largely thanks to The Lord of the Rings, the genre flowered throughout the 1960s. Many other books in a broadly similar vein were published (including the Earthsea books of Ursula K. Le Guin, the Thomas Covenant novels of Stephen R. Donaldson), and in the case of the Gormenghast books past Mervyn Peake, and The Worm Ouroboros by E. R. Eddison, rediscovered. [citation needed]

Information technology also strongly influenced the role playing game industry which achieved popularity in the 1970s with Dungeons & Dragons. Dungeons & Dragons features many races found in The Lord of the Rings most notably the presence of halflings, Elves, Dwarves, Half-elves, Orcs, and dragons. Nevertheless, Gary Gygax, lead designer of the game, maintains that he was influenced very lilliputian past The Lord of the Rings, stating that he included these elements as a marketing motility to depict on the then-popularity of the work.[33] The Lord of the Rings also has influenced Magic: The Gathering. The Lord of the Rings has also influenced the creation of diverse video games, including The Legend of Zelda,[34] Baldur's Gate, Everquest, The Elderberry Scrolls, Neverwinter Nights, and the Warcraft series,[35] equally well every bit video games set in Middle-globe itself.

As in all creative fields, a great many bottom derivatives of the more than prominent works appeared. The term "Tolkienesque" is used in the genre to refer to the oft-used and abused storyline of The Lord of the Rings: a group of adventurers embarking on a quest to save a magical fantasy world from the armies of an evil "dark lord," and is a testament to how much the popularity of these books has increased, since many critics initially decried it as beingness "Wagner for children" (a reference to the Ring Cycle) — an especially interesting commentary in lite of a possible interpretation of the books as a Christian response to Wagner.[36]

The piece of work has besides had an influence upon such science fiction authors as Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke. In fact, Clarke (who compared it to Frank Herbert's Dune [37]) makes a reference to Mountain Doom in his work 2061: Odyssey Three.[ citation needed ] Tolkien also influenced George Lucas' Star Wars films.[38]

Pop culture references

- Main article: Heart-earth in popular culture

The Lord of the Rings has had a profound and wide-ranging affect on pop culture, from its publication in the 1950s, but specially throughout the 1960s and 1970s, where young people embraced it as a countercultural saga. Its influence has been vastly extended in the present day, thanks to the Peter Jackson live-activity films. Well known examples include "Frodo Lives!" and "Gandalf for President", 2 phrases popular amongst American Tolkien fans during the 1960s and 1970s,[39] "Ramble On", "The Boxing of Evermore", and "Misty Mountain Hop", 3 compositions past the British rock ring Led Zeppelin that contain explicit references to The Lord of the Rings (with others, such as "Stairway to Sky", declared by some to contain such), "Rivendell", a song about the joys of a stay at the Elven haven by the band Rush]] (found on their album Wing by Night, 1975), "Lord of the Rings" and "Gandalf the Wizard" past the German ability metal ring Blind Guardian (who accept also produced a Silmarillion-inspired album, Nightfall in Center-Earth), most the entire discography of Austrian black metal ring Summoning (who take also looked to other Tolkien works for inspiration)[40] Rock band Marillion too take their proper noun from Tolkien's Silmarillion. The Lord of the Rings-themed editions of popular lath games (e.g., Take chances: Lord of the Rings Trilogy Edition, chess and Monopoly),[41] and parodies such equally Bored of the Rings, produced for the Harvard Lampoon.

Further reading

- Carpenter, Humphrey (2000). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography, Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-05702-1

- Prepare, William (1981). The Tolkien Relation, New York: Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-30110-8

- O'Neil, Timothy (1979). The Individuated Hobbit, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 039528208X

Run into also

- The History of The Lord of the Rings

- The Hobbit

- The Silmarillion

- Works inspired past J. R. R. Tolkien

- Adaptations of The Lord of the Rings

- Center-earth in popular culture

- Middle-earth in video games

- Themes in The Lord of the Rings

- Chronology of the Lord of the Rings

Books

- The Fellowship of the Ring

- The Two Towers

- The Return of the Male monarch

Films

- The Hobbit (1977 film)

- The Lord of the Rings (1978 movie)

- The Return of the King (1980 film)

- The Fellowship of the Ring (movie)

- The 2 Towers (picture)

- The Return of the King (movie)

Translations

| Strange Language | Translated name |

| Afrikaans | Die Here van die Ringe |

| Albanian | Kryezoti i Unazave |

| Alemannisch | Der Herr der Ringe |

| Amharic | ቀለበቶች ጌታ |

| Armenian | Մատանիների տիրակալը |

| Arabic | سيد الخواتم |

| Azerbaijani | Üzüklərin Hökmdarı |

| Basque | Eraztunen Jauna |

| Byelorussian Cyrillic | Уладар Пярсцёнкаў |

| Bengali | দ্য লর্ড অফ দ্য রিংস |

| Bosnian | Gospodar Prstenova |

| Breton | Aotrou ar Gwalennoù |

| Bulgarian Cyrillic | Властелинът на пръстените |

| Burmese | လက်စွပ်များ၏ အရှင်သခင် |

| Cambodian | ព្រះអម្ចាស់នៃកងដែល |

| Cantonese | 魔戒 |

| Catalan | El Senyor dels anells |

| Cebuano | Ang Ginoo sa mga Singsing |

| Chinese (Min Nan) | Chhiú-chí Ông |

| Chinese (Simplified) | 魔戒 |

| Chinese (Wu) | 指环王 |

| Colognian | Dr Herr dr Ringe |

| Cornish | An Arlodh a'due north Bysowyer |

| Croatian | Gospodar Prstenova |

| Czech | Pán prstenů |

| Danish | Ringenes Herre |

| Dutch | In de Ban van de Ring |

| Esperanto | La Sinjoro de la Ringoj |

| Estonian | Sõrmuste Isand |

| Faroese | Ringanna Harri |

| Filipino | Ang Panginoon ng Singsing |

| Finnish | Taru Sormusten Herrasta |

| French | Le Seigneur des Anneaux |

| Frisian | A Her faan A Ringer (Northern) Master fan alle Ringen (Western) |

| Galician | O Señor dos Aneis |

| Georgian | ბეჭდების მბრძანებელი |

| German | Der Herr der Ringe |

| Greek | Ο άρχοντας των δαχτυλιδιών |

| Hausa | Ubangijin Zobba |

| Hebrew | שר הטבעות (טרילוגיית ספרים) |

| Hindi | द लार्ड ऑफ द रिंग्स |

| Hungarian | A gyűrűk ura |

| Icelandic | Hringadróttinssaga |

| Indonesian | Raja Segala Cincin |

| Italian | Il Signore degli Anelli |

| Irish gaelic | An Tiarna na bhFáinní |

| Japanese | 指輪物語 |

| Javanese | Pangeran saka cincin |

| Kannada | ದಿ ಲಾರ್ಡ್ ಆಫ್ ದಿ ರಿಂಗ್ಸ್ |

| Kazakh | Сақиналар әміршісі (Cyrillic) Saqïnalar ämirşisi (Latin) |

| Korean | 반지의 제왕 |

| Kurdish | شای ئەنگوستیلەکان (Central Kurdish) Begê Gustîlan (Kurmanji Kurdish) |

| Kyrgyz Cyrillic | Теңир шакеги |

| Laotian | ພຣະຜູ້ເປັນເຈົ້າຂອງແຫວນໄດ້ |

| Latin | Dominus Anulorum |

| Latvian | Gredzenu pavēlnieks |

| Lithuanian | Žiedu Valdovas |

| Lombard | El Scior di Anei |

| Luxembourgish | Den Här vun de Réng |

| Macedonian Cyrillic | Господарот на Прстените |

| Maithili | द लर्ड अफ द रिङ्ग्स |

| Malaysian | Raja Segala Cincin |

| Maltese | Il-Ħakkiem ta 'l-anelli |

| Maori | Te Ariki o nga Mowhiti |

| Marathi | द लॉर्ड ऑफ द रिंग्स |

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Бөгжний эзэн |

| Montenegrin | Gospodar Prstenova |

| Nepalese | द लर्ड अफ द रिङ्ग्स |

| Norwegian | Ringenes Herre (Bokmål) Ringdrotten (Nynorsk) |

| Occitan | Lo Senhor dels Anèls |

| Quondam English language | Se Hlāford þāra Hringa |

| Pashto | د کړۍ_ګانې رب |

| Farsi | ارباب حلقه ها |

| Smoothen | Władca Pierścieni |

| Portuguese | O Senhor dos Anéis (Brazil) A Irmandade exercise Anel (Portugal) |

| Punjabi | لارڈ آف دا رنگز (Western Punjabi) ਦ ਲਾਰਡ ਆਫ਼ ਦ ਰਿੰਗਸ |

| Quechua | Siwikunap Apun |

| Querétaro Otomi | Ar 'ño̲ho̲ ya anillos |

| Romanaian | Stăpânul Inelelor |

| Russian | Властелин колец |

| Sardinian | Su Sennore de sos Aneddos |

| Scottish Gaelic | Tha Tighearna nam Fàinnean |

| Serbian | Господар прстенова (Cyrillic) Gospodar Prstenova (Latin) |

| Sinhalese | ද රින්ග්ස් සමිඳාණන් |

| Slovak | Pán Prsteňov |

| Slovenian | Gospodar Prstanov |

| Spanish | El Señor de los Anillos |

| Sundanese | Gusti tina Cingcin |

| Swahili | Bwana wa Mapete |

| Swedish (old) Swedish (new) | Härskarringen Ringarnas Herre |

| Tajik Cyrillic | Парвардигори зиреҳҳои |

| Telugu | ఆ లార్డ్ ఆఫ్ ది రింగ్స్ |

| Tamil | த லோட் ஒவ் த ரிங்ஸ் |

| Thai | ดออฟเดอะริงส์ |

| Turkish | Yüzüklerin Efendisi |

| Turkmen | Ýüzükleriň Padşasy |

| Ukrainian Cyrillic | Володар перснів |

| Urdu | دی لارڈ آف دی رنگز |

| Uzbek | Узуклар Ҳукмдори (Cyrillic) Uzuklar Hukmdori (Latin) |

| Vietnamese | Chúa tể những chiếc nhẫn |

| Welsh | Yr Arglwydd y cylchoedd |

| Yiddish | דער האר פון די רינגס |

| Yucatec Maya | Le Máako' le anillos |

| J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-earth Legendarium | |

|---|---|

| | The Hobbit (1937) • The Lord of the Rings (The Fellowship of the Ring [1954] • The 2 Towers [1954] • The Return of the Male monarch [1955]) • The Adventures of Tom Bombadil [1962] • The Road Goes Always On [1967] |

| | Bilbo's Last Song [1974] • The Silmarillion [1977] • Unfinished Tales [1980] The History of Heart-earth (The Book of Lost Tales Part Ane [1983] • The Book of Lost Tales Part 2 [1984] • The Lays of Beleriand [1985] • The Shaping of Centre-earth [1986] • The Lost Route and Other Writings [1987] • The Render of the Shadow [1988] • The Treason of Isengard [1989] • The State of war of the Ring [1990] • Sauron Defeated [1992] • Morgoth'southward Ring [1993] • The War of the Jewels [1994] • The Peoples of Middle-earth [1996] • Index [2006]) Great Tales (The Children of Húrin [2007] • Beren and Lúthien [2017] • The Fall of Gondolin [2018]) The Nature of Middle-earth [2021] Articles about Middle-world past... |

References

Text

- Tolkien, J.R.R. (1954 [2005]). The Lord of the Rings. Houghton Mifflin.

paperback: ISBN 0-618-64015-0

- Tolkien, J.R.R. (1937 [2002]). The Hobbit. Houghton Mifflin.

paperback: ISBN 0-618-26030-7

- Tolkien, J.R.R. (1977 [2004]). The Silmarillion. Houghton Mifflin.

paperback: ISBN 0-618-39111-8

- ↑ World War I and World War II. Retrieved on 2006-06-16.

- ↑ Tolkien FAQ: How many languages have The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings been translated into?

- ↑ 3.0 three.i three.ii iii.3 iii.4 3.5 3.half dozen Tolkien, J.R.R. (1981). The Messages of J. R. R. Tolkien. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-05699-8.

- ↑ Exploring the Diverse Lands of Middle-globe. Retrieved on 2006-06-sixteen.

- ↑ The Return of the King: Summaries and Commentaries: Appendices. Retrieved on 2006-06-xvi.

- ↑ J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biographical Sketch. Retrieved on 2006-06-16.

- ↑ Gilliver, Peter (2006). The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English language Lexicon. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-nineteen-861069-six.

- ↑ 8.0 eight.1 Gilsdorf, Ethan (November sixteen, 2003). Lord of the Gold Band. The Boston Globe. Retrieved on 2006-06-xvi.

- ↑ 9.0 nine.i 9.2 9.three 9.4 ix.five 9.vi 9.7 9.viii The Lord of the Rings: Genesis. Archived from the original on 2003-08-17. Retrieved on 2006-06-14.

- ↑ Tom Shippey, The Road to Middle-globe Revised and Expanded Edition

- ↑ Tom Shippey, J.R.R. Tolkien: Writer of the Century

- ↑ Tom Shippey, J.R.R. Tolkien: Writer of the Century, Ch. 2, pg. 54

- ↑ The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Alphabetic character 131, pg. 145

- ↑ Socher, Abe (April nineteen, 2005). Grading Blues. Relate Careers. Retrieved on 2006-04-22.

- ↑ Tolkien, J.R.R. (2000). The State of war of the Ring: The History of The Lord of the Rings, Part 3. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-08359-6.

- ↑ How many languages have The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings been translated into?. Retrieved on 3 June 2006.

- ↑ Influences of Lord of the Band. Retrieved on 16 April 2006.

- ↑ Steven D. Greydanus. Faith and Fantasy: Tolkien the Catholic, The Lord of the Rings, and Peter Jackson's Flick Trilogy. Retrieved on 4 June 2006.

- ↑ Cultural and Linguistic Conservation. Retrieved on 16 April 2006.

- ↑ The LOTR Props Exhibition: Steve la Hood Speaks. Retrieved on 14 June 2006.

- ↑ Tolkien, J.R.R. (1991). The Lord of the Rings. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-261-10238-9.

- ↑ From the Critics. Retrieved on May thirty, 2006.

- ↑ Hobbits in Hollywood. Retrieved on May 13, 2006.

- ↑ Richard Jenkyns. "Bored of the Rings." The New Republic. January 28, 2002. [1]

- ↑ Wilson, A.N.. "Tolkien was not a writer", telegraph.co.uk, Telegraph Group Express, 2001-eleven-24. Retrieved on 2013-eleven-30.

- ↑ We Hobbits are a Merry Folk: an incautious and heretical re-appraisal of J.R.R. Tolkien. Retrieved on ix January 2006.

- ↑ Moorcock, Michael. Epic Pooh. Retrieved on 27 January 2006.

- ↑ J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biographical Sketch. Retrieved on June 14, 2006.

- ↑ Seiler, Andy (December 16, 2003). 'Rings' comes full circumvolve. USA Today. Retrieved on 2006-03-12.

- ↑ Cooper, Callista (Dec five, 2005). Epic trilogy tops favourite film poll. ABC News Online. Retrieved on 2006-03-12.

- ↑ O'Hehir, Andrew (June four, 2001). The book of the century. Salon.com. Retrieved on 2006-03-12.

- ↑ Diver, Krysia (Oct v, 2004). A lord for Germany. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved on 2006-03-12.

- ↑ Gary Gygax - Creator of Dungeons & Dragons. Retrieved on 2006-05-28.

- ↑ (1996) Gild Nintendo (Frg). Nintendo of Europe. "Takashi Tezuka, a great lover of fantasy novels such as Tolkien's Lord of the Rings, wrote the script for the first two games in the Zelda series."

- ↑ Douglass, Perry (May 17, 2006). The Influence of Literature and Myth in Videogames. IGN. Retrieved on 2006-05-29.

- ↑ The Complete Spengler. Asian Times Online (May 29, 2006). Retrieved on 2006-05-29.

- ↑ http://world wide web.iblist.com/book.php?id=130

- ↑ Star Wars Origins - The Lord of the Rings. Star Wars Origins. Retrieved on 2006-09-19.

- ↑ Carpenter, Humphrey (2000). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-05702-i.

- ↑ White Dwarf Mag, #304

- ↑ Drake, Matt (June 29, 2005). Review of Lord of the Rings. RPGnet. Retrieved on 2006-05-29.

Source: https://lotr.fandom.com/wiki/The_Lord_of_the_Rings

0 Response to "Lord of the Rings the Towers Book Cover Lord of the Rings All Four Books Art Project"

Post a Comment